Orpheum descending

Sunday | July 15, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

State Street, Madison, Wisconsin, 1927.

DB:

When it comes to film culture, Wisconsin yields to no one in weird-assery. I’ve chronicled Mad City Movie Mania on other occasions (here and here), and a current flap has just added to the annals of the addled.

It revolves around Madison’s Orpheum Theatre, a 1927 movie palace that has gone through many incarnations. In recent years it’s become mainly a music venue, but it was also fitted out with a restaurant and still showed the occasional art movie. Until it was shut down last month.

The problem is that after several years of confusion, feuding, moving money around, petty spite, and general dodginess, nobody knows exactly who owns the Orpheum. Is the owner Henry Doane, local restauranteur, who for years was publicly considered the purchaser? Is it Eric Fleming, Doane partner who became anything but silent? Is it Gus Paras, wealthy landlord and restauranteur, who bid a couple of million for it at auction last month? What of the woman who acquired Fleming’s share of the building? And the shadowy figure who made off with a plastic bag holding $175,000—how does he fit in?

“I’ve never done anything to deserve the negative treatment that I’ve been getting. I’m very compromising. I’m willing to do whatever it takes to make things work—as long as it’s profitable.” Eric Fleming

“I’ve gone through every kind of humiliation known to mankind, so I’m kind of immune to it at this point.” By 2007 the partnership had gone so sour that Doane keyed Fleming’s car in broad daylight.

Please visit the story by Steven Elbow at the Capital Times for all the details. My account will be drawing on Elbow’s patient sleuthing, but I also want to recall the glorious, not to mention the inglorious, days of this old house.

Marbles

Orpheum Theatre, 1927. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

Designed by Rapp and Rapp, premiere theatre architects, the New Orpheum opened in 1927. (It was initially called that because it superseded the Orpheum, a vaudeville house in another part of town, which was soon renamed the Garrick and specialized in live theatre.) The New Orpheum’s lavish French Renaissance foyer swept up to a staircase leading to the balcony. The auditorium held over 2400 seats, making it the biggest theatre in town until the slightly larger Capitol was built across the street a year later, also by Rapp and Rapp.

The New Orpheum (hereafter, the Orpheum) was one of those picture palaces that aimed to elevate the filmgoing experience while also being a good community citizen. It had a corps of ushers, a smoking lounge, and a reputation for punctilious service. The theatre sponsored community events too. When the local newspaper launched a marbles tournament, the Orpheum held a screening for 2000 kids.

The kids came early and jammed the State street side of the New Orpheum, so it was necessary to call extra policemen to handle the traffic. Once inside the theatre they yelled and applauded the two comedy features which were shown for them, and practically jumped out of their seats during the showing of “Why Sailors Go Wrong.”

Six months before the 1929 stock market crash, the Orpheum was reportedly selling 20,000-25,000 tickets per week, in a town of about 55,000 souls.

An RKO town

View from the Orpheum stage, Halloween, 1930. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.

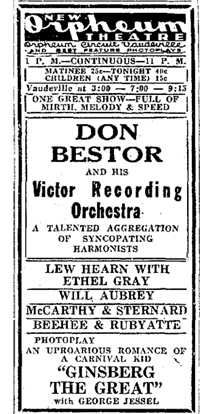

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

The New Orpheum and the Capitol weren’t in competition, since the Keith-Albee vaudeville circuit owned both. Both houses showed movies, but they seem to have been secondary at the Orpheum. Sometimes Orpheum ads from the late 1920s don’t even mention the titles of what’s playing. (This ad on the right is from 1928.) When talkies came in and the circuit became part of Radio-Keith-Orpheum, films became the central attraction, with live performances as filler. A 1930 kids’ party at the theatre shows the banner flying, “These Madison Boys and Girls Are on their Way to an RKO Theatre.”

Despite the Great Depression, RKO moved quickly to monopolize the Madison movie scene. In 1931, the Parkway (capacity 1100) was acquired by the chain, and soon afterward RKO cut a deal with the Fox Film Corporation to take over the Strand (1400 seats). The swap permitted Fox to dominate Milwaukee in exchange for making Madison an RKO town for first-run films. Of course, in good oligopolistic fashion the RKO theatres showed films from all the studios, as did the second-run houses.

I’ve been unable to determine at what point RKO lost control of its Madison screens. [But see the P. S. below.] Presumably it was after the 1948 divorcement decrees severed Hollywood studios from control of theatres. At some point the Milwaukee entrepreneur Dean Fitzgerald acquired seven local houses, including the Orpheum, under the rubric of the Madison Twentieth Century Theater Corporation.

In 1969, a second screen was carved out of the backstage area of the Orpheum and the minuscule theatre that resulted was called the Stage Door. The contrast with the imposing classic house was startling: the Stage Door was almost certainly the worst theatre in town. Then it declined even more. By the end, with its spidery movable chairs and dank atmosphere, it was reminiscent of the storefront theatres of the nickelodeon era, except that they were surely more comfortable.

Less than heavy traffic

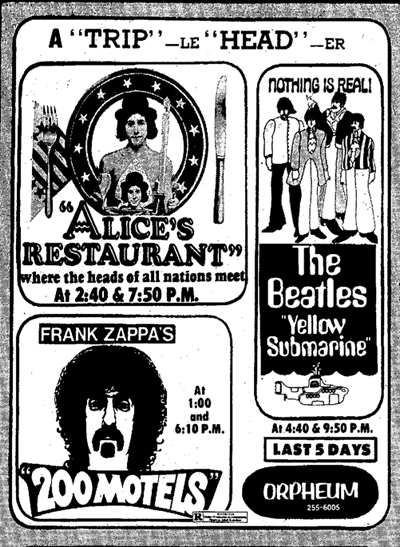

Capital Times advertisement, September 1973.

When Kristin and I came to Madison in 1973, we saw a sort of Sargasso Sea of old movie houses. The Majestic, a decrepit vaudeville house built on a plan as cockeyed as an Escher drawing, was showing X-rated fare, kung-fu, and double-bill repertory. It became a Landmark calendar house. A neighborhood house, the Atwood (aka the Eastwood and the Cinema), built in 1930, screened porn and kiddie shows , though not together. The Esquire also offered sex: arty (The Story of O) or not (Dr. Feelgood, with Harry Reems). The mammoth Strand was still functioning as a first-run house; Star Wars played there for months. The Middleton (seating 500 or so) was designed as a Quonset hut in 1946, and was said to have been built in a week. By our day it was playing second run. The Capitol, where I saw The Exorcist, was still operating too. Every year one theatre or another seemed to run the endlessly popular Eastwood Dollars trilogy.

The mall cinemas were emerging as single-screeners or duplexes. They got the premiere first-run pictures like The Sting, often leaving the downtown houses with lesser items. The most obvious options were counterculture movies and sexploitation.

The Orpheum went along. “Entertainment for the Entire Family!” trumpeted a 1965 Orpheum ad, but by 1969 there were revivals of Bullitt and Bonnie and Clyde. Sometimes classier items like The Godfather would show up in second run, but Orpheum fare in the early seventies was more likely to be Heavy Traffic, Enter the Dragon, The Filthiest Show in Town, revivals of headflix (see above), and a double-bill of Russ Meyer’s Vixen and Up! This was the period when the movie page of the papers included ads for This Is Heaven Sauna Massage, The Rising Sun Counseling Clinic (Adults Only), Photographic Arts Do It Yourself Nude Photography (Camera and Film Supplied), Ms. Brews Lounge (Nude Dancing Daily), and The Dangle strip club.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

One by one the theatres were closed or converted to other uses. The Capitol became part of an arts complex. The Orpheum remained the only more or less intact movie house from the old days. By 1998, Dean Fitzgerald was ready to sell it.

Two forces were contending for the property. As part of a plan to revitalize the downtown area, the Madison Idea Foundation proposed putting in an IMAX facility. But preservationists objected that an IMAX setup would wreck the layout of the house. By contrast, restaurant owner Henry Doane (right) favored restoration. He proposed to rehabilitate the old place respectfully and use it for art films, film festivals, and live music. He also wanted to install an upscale café and bar.

Doane won the City Council’s approval and in 1999 he purchased the Orpheum. Throughout the 2000s, thanks to some clever programmers, it played remarkably eclectic fare, from Arnaud Depleschin ‘s A Christmas Tale to Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle (running two weeks, no less). In addition, Doane’s plan to revive the Orpheum as a live music venue, with booze, was finding some success. The grand house that had hosted Gene Krupa, Frank Sinatra, Bob Marley, and Journey now had popular indie bands. When local critic Rob Thomas drew up his list of ten-best shows for the decade, Orpheum concerts took five places. Most memorably, Bela Fleck and the Flecktones played to a packed house the night after the World Trade Tower attacks, highlighted by a version of “God Bless America.”

Drinks plus dining plus music kept the Orpheum doors open, but by the late 2000s the place was obviously not flourishing. There were rumors that distributors, long unpaid, were withholding films. The place was becoming disheveled, with seats broken, that stratospheric ceiling ominously peeling, and the sound system a fog of distortion.

Worse, even though most Madisonians had an affection for the old house, nobody much went there to watch a film. Things had started promisingly: Doane’s introduction to the movie business was the blistering summer of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace and The Blair Witch Project. But that was an atypical season. During the 2000s, most of the biggest audiences showed up during the Wisconsin Film Festival. It was indeed thrilling to see the place packed out for classics like A Hard Day’s Night (introduced by Roger Ebert) and imports like The Foul King and Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself (both shown in the presence of the directors).

At some point, accommodations were made to favor the concerts: front rows were ripped out to provide dance space.

It became a wretched place to watch movies. Lobby dance parties during screenings could drown out the soundtrack. District 13 was projected within a rectangle framed by a scaffolding erected for an upcoming show. As the decade wore on, you might go to the Orpheum for music, but you didn’t go for the films.

Orpheum vs. Orpheum

Now we know a bit more about what happened behind the scenes in the 2000s. At some point Doane split ownership of the Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison 50-50 with Eric Fleming, a real-estate and restaurant operator.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming (right) is the sort of fellow who gets called “colorful.” He first made it into the Madison press when he opened Crave, a self-consciously hip restaurant noted for its martinis. “People come here to be out and get a little dressed up,” he told one reporter. “Kind of like a ‘Sex and the City’ place.” Maybe a little too much so: A year later Fleming was charged with disorderly conduct for pouring a drink over a Crave customer and groping a female patron. In December 2008, after an altercation that started in the restaurant, one customer was killed on the street by another in the presence of a Crave bouncer.

Fleming’s business style is traced in Elbow’s article. After Fleming became co-owner of the Orpheum, a busted real-estate investment required him to pay creditors $1.5 million. Seeking to dislodge Doane, he created a new company, Orpheum of Madison, claiming that entity as the functioning business arm. He folded that into a package of assets he transferred to Ms. Olesya Kuzmenko for $175,000. “This is what I do for a living,” Fleming explains in Elbow’s article. “I create things and I sell them.”

Who is Kuzmenko, who wound up with a mammoth downtown theatre for the price of a small house on the outskirts of town? She is believed to be Fleming’s girlfriend, but beyond that little is known. She is listed on a license application as President, Vice-President, Secretary, Treasurer, Director, and sole stockholder in Orpheum of Madison. A few years before, Fleming had sold Crave to Christina Bishop, his secretary and girlfriend at the time, under the rubric of a new company Evarc (Crave spelled backward).

There were some curious incidents over these years. There were three fires at the Orpheum, at least two considered by the police to be arson. So far no arrests have been made in the cases. There was also reportedly a break-in, during which a computer was stolen. Perhaps the strangest incident involves the fate of Kuzmenko’s payment. Elbow’s article reports Fleming’s account:

He withdrew the $175,000 he got from Kuzmenko in $100 bills from his bank account, put the cash in a plastic bag and handed it over to a guy identified in court records as Marcus DaMarko, and never saw it again.

“I loaned somebody money,” says Fleming. “I loaned him some money to invest in something. I haven’t talked to him since so I don’t have the money currently.”

So, a reporter asks, you were taken?

“Essentially.”

One more for the road

Because of these maneuvers, Fleming has been running the Orpheum for over a year without input from Doane. The newest issue involves alcohol.

Wisconsin, you must understand, has a frenzied drinking culture. We lead the nation in binge drinking, drinkers per capita, heavy drinkers per capita, and drunk driving. Madison’s main downtown artery, State Street, is packed with bars and restaurants, and the UW’s reputation as a party school attracts an endless supply of youths eager to get wasted. Consequently, what state law calls “alcohol beverages” have been central to the revival of the Orpheum. To establish the lobby restaurant (above) Doane needed to serve beer, wine, and spirits. And Fleming’s cash flow in recent years has been boosted by numerous weddings, which demand booze.

But over the years, the Orpheum’s state vendor’s permit and its liquor license have become problematic. Just during the fall of 2006, the venue under Fleming’s management accumulated some 200 points of alcohol-related violations, and there was a demand that its license be suspended. Across the spring months of 2011, things became more dramatic.

In a series of appeals to the Alcohol License Review Committee of the Common Council, Fleming began to press for the Orpheum’s liquor license to be transferred to his company, Orpheum of Madison. He assured the ALRC that Doane’s original company, Orpheum Theatre Co. of Madison, would be evicted from the premises. Doane replied he knew nothing about this, and indeed he was not evicted. Moreover, he argued that Fleming was making purchases for his own company but billing their original one. And Fleming, he claimed, had changed the door locks. The ALRC, declining to step into the middle of the feud, decided to let Doane’s original company hold the license until ownership was clarified.

Auction fever

That fracas took place a year ago, but things really got going this spring. While Doane was suing Fleming to regain control of the building, the Orpheum faced foreclosure because of unpaid bills. In April it went on the auction block.

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Enter Gus Paras (right), once Fleming friend and now Fleming foe. “He sued me and cost me a lot of money,” Paras explained. “The other thing is I watched people he screwed so bad he put them on their knees.”

Gus Paras had had many dealings with Fleming when both sought to buy property in the area. Now Paras wanted the Orpheum as well. But when the property went to auction, along with the 300 block that had also been part of the Fleming/ Kuzmenko package, Olesya Kuzmenko showed up and began bidding against Paras. In a scene reminiscent of the auction in North By Northwest, she bid the price for the Orpheum up to $1.9 million, but Paras won it for $2.25 million. She bid again on the 300 block properties, but Paras bid her up and then folded, leaving her stuck with her $2.25 million bid. But she couldn’t make the down payment, so the court gave both the Orpheum and the 300 block to Paras for $1.9 million each. However, as of this writing, the sale has not yet been consummated. A court will need to determine who actually owns the building.

In the meantime new alcohol problems resurfaced. Doane requested that the Orpheum’s state seller’s permit not be reactivated. It expired. But the Orpheum continued to sell booze. For a time it seemed that every drink poured since April 2011 had been in violation. A June 2012 story explained:

[Assistant City Attorney Jennifer] Zilavy said the Orpheum should not have served alcohol at concerts and other events. She isn’t sure if the city will pursue civil charges, which could result in a $1,000 fine for each infraction, or refer the matter for criminal charges, which could result in a fine of up to $10,000 or nine months in jail per offense.

As a result, last month the Common Council of the city declined to renew the Orpheum’s liquor license. When the police tried to serve notice of non-renewal, they were unable to rouse anyone. “It is locked up, lights out, nobody there,” reported the officer. Now, however, it seems that Fleming managed to re-activate the license fairly soon after Doane deactivated it, so it’s unclear how long, if at all, the Orpheum was serving drinks illegally.

The city later discovered that Fleming, nothing if not tenacious, was at some point granted a state seller’s permit for his new company. But as of early July the sort-of-partners remained at loggerheads. Doane’s company had a liquor license but no seller’s permit. Fleming’s company now has a seller’s permit but no liquor license. And Doane’s company’s liquor license expired last Saturday. The Madison Common Council has sent the matter to the ALRC for a public hearing. possibly as soon as next week.

I wish I could answer every question that’s come up. Who is Mr. DaMarko, and what became of the 1750 $100 bills? If Paras finally acquires the building, what status does Fleming’s operation have with respect to it? What about Doane’s stake in the theatre he originally bought?

One thing seems certain: If the old place resumes operations, it will be as a venue for weddings and live music, with a bar and perhaps a café. As movies evicted vaudeville from the Orpheum in the 1930s, so now live performance has replaced movies. The drama and comedy have moved off the screen into the streets, the Common Council, and the halls of justice.

Steven Elbow follows up his main story here. If anything develops, he will probably report on it in his blog.

The Orpheum website reflects the chaotic state of its circumstances. Videos of the ALRC hearings, from which my three portraits of the protagonists are taken, may be streamed here and here. In late June, Eric Fleming conducted a brief video tour of the Orpheum’s restorations. The most recent application from Kuzmenko’s company requests that the liquor license begin on 1 July 2012 and end on 30 June 2012. Will the fun never stop?

Some accounts date the Orpheum from 1926, but it opened in March 1927. (See, for example, “New Orpheum’s First Birthday Cake,” The Capital Times, 3 April 1928, 3.) To view more magnificent Orpheum photos from the Wisconsin Historical Society collection, go here. The color shot of the Lobby Restaurant is from the Onion. (The Onion originated–where else?–in Madison.) The color shot of the missing front rows is from the 2010 Wisconsin Film Festival. For a sense of what a wedding looks like in the Orpheum, go to Valo Photography.

Wisconsin’s mad flight from sobriety is documented in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel‘s award-winning series. As far as I know, nothing much has changed since that 2008 survey.

This has been my Year of Living Exhibitionistically; see the Pandora posts and the e-book for accounts of different movie theatres. Older entries are here and here.

P.S. 15 July 2012: Douglas Gomery writes that RKO probably lost its grip on the Orpheum and other theatres much earlier than I speculated:

The Film Daily Yearbook of 1931 lists RKO holdings in Wisconsin: Madison, the Capitol & Orpheum; Milwaukee, the Riverside; and Racine, the Downtown (literally). In 1932 RKO goes into bankruptcy, and all its Wisconsin holdings disappear from FDY. My guess is that the Orpheum and other houses became locally owned.

Douglas wrote the definitive book on American exhibition, Shared Pleasures, and I thank him for the correction.

P.P.S. 16 July: My original post indicated that Kuzmenko won the Orpheum temporarily before she proved unable to make the down payment. Steve Elbow corrected my claim on this: what she acquired at auction was actually the 300 block property, which had been folded with the Orpheum into the overall property Fleming sold her for $175,000. Gus Paras bid successfully on the Orpheum itself.

The blog has been revised to reflect another piece of information Steve provided me: that Fleming may have reactivated the Orpheum’s liquor license quite soon after Doane deactivated it. Thanks to Steve for these corrections.

P.P.P.S. 27 May 2013: A query from Laura Ursin has led me to correct the date in the caption of the top photo, which I had dated from 1938.

The Orpheum Theatre under construction, 1926. Photo by Angus B. McVicar. Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society.